Published October 2020

Summary

As we get older, our senses change, including our sensitivity to temperature. People living in care homes don’t have control over their environment, and may not be able to determine or communicate if they’re uncomfortably warm or cold. Professor Charmaine Childs used thermal imaging to understand how people’s physical temperatures compared with how they felt, and whether this was affected by dementia.

An interesting research question

I’ve previously worked with thermal imaging cameras in research relating to body and brain temperature regulation following head injury and also to identify wound infections after surgery. But my interest in the temperature regulation of older people came about when visiting my parents: despite living in the same environment, they reported very different perceptions of whether the indoor temperature was comfortable or not.

It got me thinking about the variation in temperature perception by older people living in the same environment – particularly people living in care homes where many older people live together yet have little or no control over the environmental temperature.

We know that senses change as we get older, and this also applies to a person’s sensitivity to temperature. So we wanted to investigate whether people’s perceptions of their thermal comfort matched what the thermal imaging showed, and if this changes when someone has dementia.

What did we do?

We recruited 60 people living in care homes for our study, half of whom had dementia and half who did not. For participants with dementia, we carried out cognitive assessments to check they were able to effectively communicate how comfortable they were feeling.

Thermal comfort scales have tended to be used in healthy, young people in office environments, but they aren’t typically used in care homes

Professor Charmaine Childs, Principal Investigator

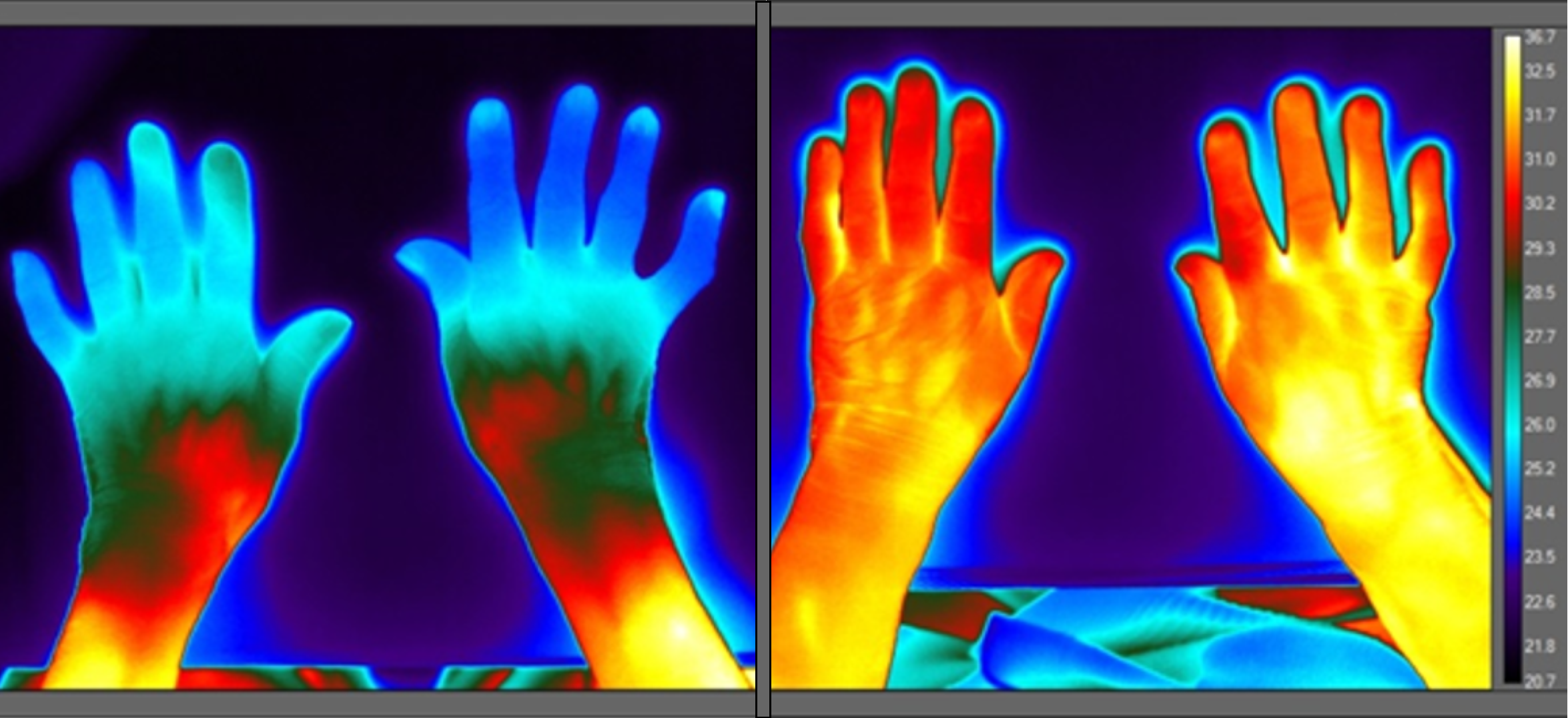

My research assistant and I measured participants’ temperatures with the thermal imaging camera. We also took images of their hands on a table, and looked at their fingertips, wrists and forearms to see how they were affected by the room temperature.

We also asked the participants whether they were comfortable, or too hot or too cold by asking them to rank how they felt on a ‘thermal comfort scale’. These scales have tended to be used in healthy, young people in office environments but they aren’t typically used for older people in care homes.

The care homes in our research were all between 21.6 and 26 degrees Celsius, but we found that the thermal imaging varied between residents in the same homes, with people with dementia tending to be colder.

Furthermore, the residents’ reporting of their thermal comfort didn’t always correspond to what was happening to their bodies according to the camera. Although people with dementia did have lower skin temperatures than those without dementia, a lot of them still said that they felt comfortable even though the camera suggested that their extremity skin was cold. This raises questions about the effect of dementia in ‘blunting’ thermal sensitivity, as well as the variation in individual comfort levels.

We presented this work to public health workers, policy makers and others interested in the care of older people at a consensus workshop, with the aim of moving forward recommendations to ensure indoor comfort for older people. A representative from the Dunhill Medical Trust came along to the workshop – it was really nice that they took the time and effort to join us and learn about our findings.

We’re currently working with designers, engineers and architects to create simple thermal imaging camera systems that could be easily used in care homes, and are hoping to gain funding to continue this work.

Not all smooth sailing

Getting care homes to join the study and recruiting participants was harder than we anticipated. We had originally planned to recruit four care homes to get the number of participants that we needed, but ultimately needed to recruit 15.

The DMT trusted that we could deliver on the study, which kept me going throughout the project. If you’ve got a good funder, it makes you determined to get the work done, despite the inevitable ups and downs

Although this initially led to a delay in recruitment, the Dunhill Medical Trust were really understanding and helpful. And when we had problems setting up the study, they were very supportive. It made me feel like there was someone who knew and understood how difficult research in this area can be.

Find out more

We produced a booklet for our consensus workshop, providing some background on the sessions and the invited speakers. You can read this here.

A recent open access publication, based on our findings, is available to read in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.